SBMF has a rich and significant history, rooted in a legacy of innovation and growth. From its beginnings in 1912 as the South Bend Medical Laboratory, the organization has played a vital role in providing laboratory services to the local community. In this two-part series, we will go into the history of SBMF, and explore how it began with a vision and evolved into the renowned institution it is today.

It Began with a Vision

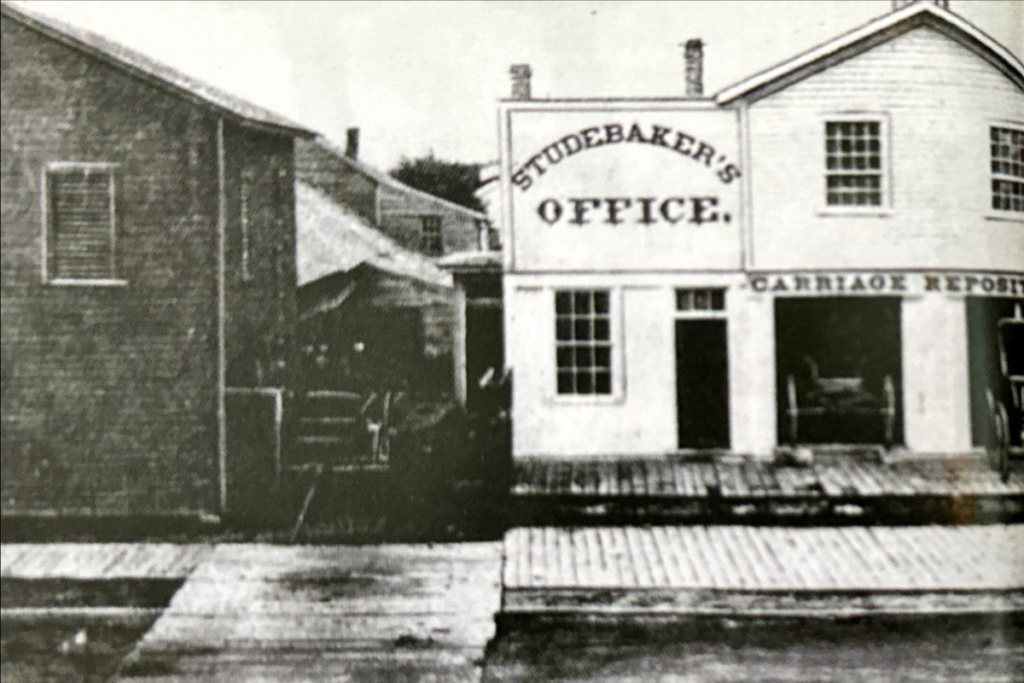

In 1912, the city of South Bend experienced rapid growth during the Industrial Revolution. With the transition of the Studebaker Corporation from horse-drawn wagons to gasoline automobiles and the relocation of the South Bend Zoo to Potawatomi Park, there was a growing need for local laboratory services to support the expanding population and advancing industries.

Recognizing this need, 23 doctors in South Bend came together to establish the South Bend Medical Laboratory. This group of physicians understood the importance of having accessible and reliable laboratory services to support healthcare delivery and provide accurate diagnoses for patients in the growing community. Their initiative led to the establishment of the South Bend Medical Laboratory, which would later evolve into SBMF.

Early Leadership

circa 1915

circa 1927

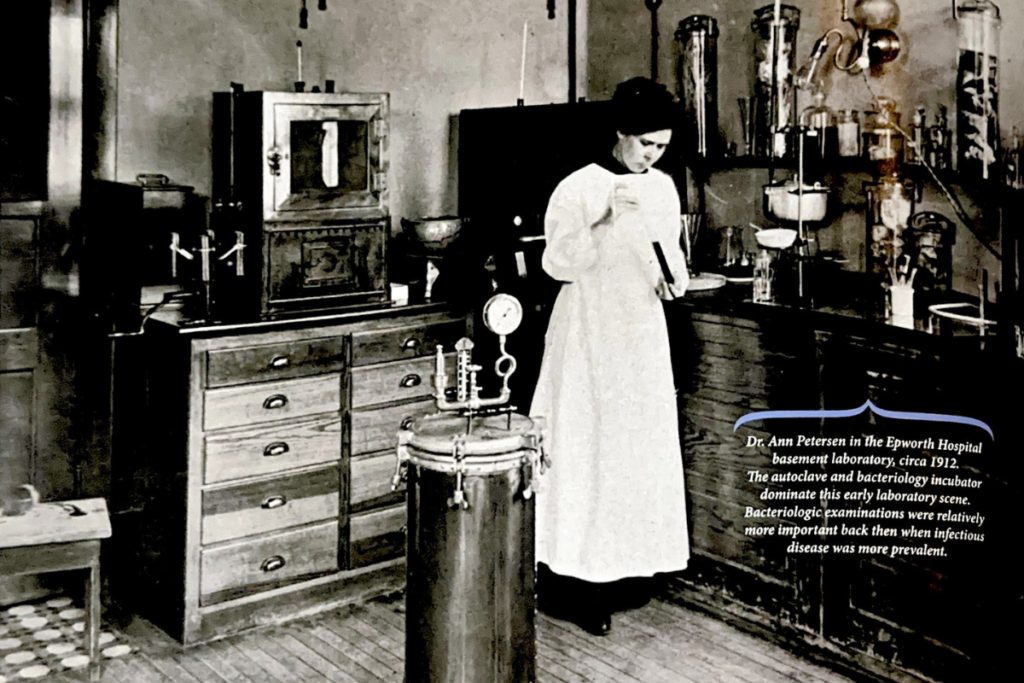

South Bend Medical Laboratory was a forward-thinking organization from its inception and demonstrated this by appointing Dr. Ann Petersen as its first director – a trailblazing position for a woman in a field traditionally dominated by men. Dr. Petersen, with her medical education in Germany and experience in pathology at the Iowa State Laboratory, brought a unique perspective to the laboratory’s operations. Operating from a former sewing room in Epworth Hospital, the Laboratory provided rapid diagnoses to local physicians, thanks in large part to the pioneering leadership of Dr. Petersen.

The Laboratory faced challenges early on, but the relentless advocacy of Dr. Stanley Clark, a founding physician, kept it afloat. Dr. Clark emphasized the importance of diagnostic laboratory testing and paved the way for the Laboratory to become a testing site for public health issues, particularly tuberculosis. In 1914, the Laboratory signed contracts with the cities of South Bend and Mishawaka to test indigent patients and examine drinking water, milk, and food for diseases.

In 1915, Dr. Petersen resigned, and Dr. James Gooken became director. Under Dr. Gooken’s leadership, the Laboratory made significant advancements in combating diseases. For example, Dr. Gooken discovered a serum to combat morning sickness and was instrumental in controlling diseases in the city. In 1917, the Laboratory confirmed Balantidium coli bacteria in the local water supply, leading to the shutdown of South Bend’s North Reservoir for cleaning.

In 1920, the Laboratory expanded its space at Epworth Hospital (now known as Beacon Memorial Hospital) and even created a museum of pathologic specimens. This marked the beginning of a century-long pattern of innovation and growth for the Laboratory.

The Giordano Years

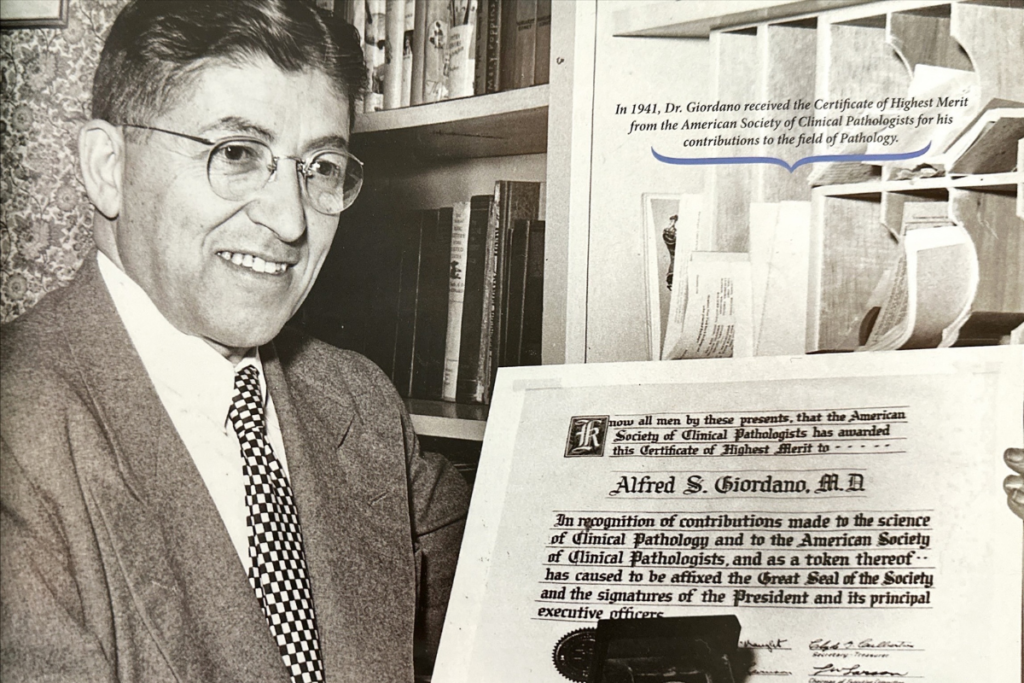

In 1922, Dr. Alfred Giordano became the medical director of the South Bend Medical Laboratory. Dr. Giordano’s tenure was characterized by breakthrough research on milk-borne disease and testing for sexually transmitted diseases.

Dr. Giordano’s interest in milk safety grew after his colleague, Dr. Stanley Clark, fell seriously ill with undulant fever. Further testing revealed the source of the infection was raw milk. Dr. Giordano developed a skin reaction test for undulant fever and advocated for mandatory pasteurization of milk, leading to a decline in the disease nationwide.

During Dr. Giordano’s tenure, the Laboratory faced increased demands for services. It moved to a new location to 530 North Lafayette Boulevard in 1932 and underwent several expansions. In 1946, the organization changed its name to the South Bend Medical Foundation, reflecting its non-profit status.

Dr. Giordano’s impact extended beyond the Laboratory. He served as the secretary-treasurer of the American Society of Clinical Pathologists and played a crucial role in advancing the field of clinical pathology. After his resignation as medical director in 1952, Dr. Giordano remained a consultant for SBMF. Dr. Giordano’s legacy at the SBMF can still be seen and felt in the halls of the organization. Appropriately his portrait hangs in the conference room and the prestigious Giordano Lecture Series is named in his honor.

Epidemics and Enterprises

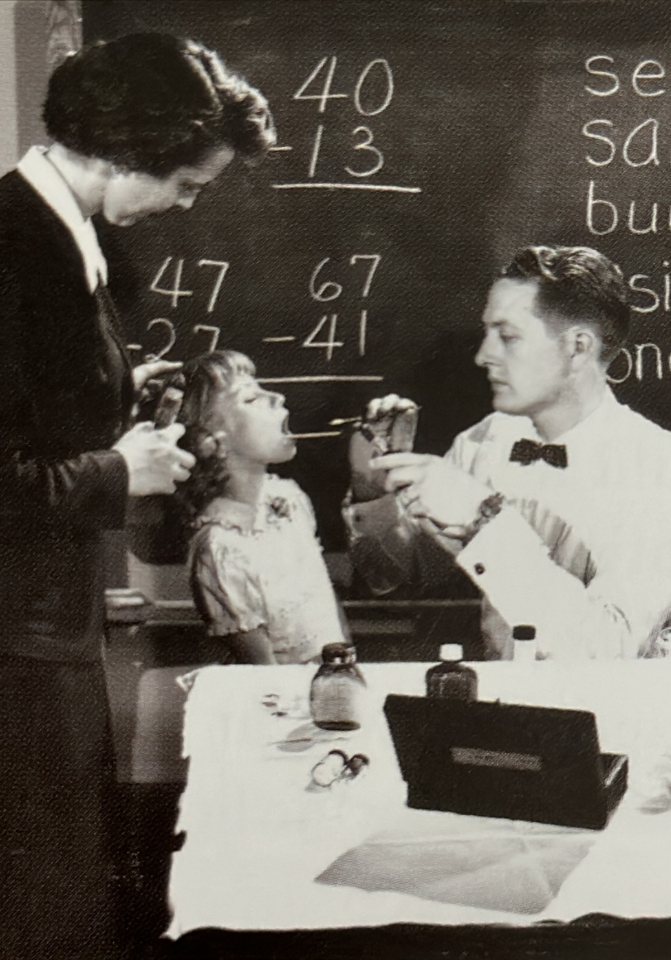

Throughout the decades, SBMF has been called upon repeatedly to take a leadership role in protecting public health against real and potential epidemics. Take, for example, the 1930 outbreak of cerebrospinal meningitis. Meningitis caused many fatalities including, sadly, 34-year-old Marjorie Ableson, a technician and bacteriologist at the Laboratory. Ableson died as a result of her work, contracting the disease while examining throat cultures in the lab. SBMF joined forces with the city of South Bend and public health officials in examining throat cultures of school children and others suspected of having the disease, as well as instituting ordinances that barred all children under the age of 14 from movie theaters and public gathering places.

In the middle of the 20th century, another epidemic also prompted the closing of numerous schools, churches and theaters. The name of the disease was infantile paralysis, though more commonly referred to as polio. SBMF responded to the polio crisis on many fronts. Onsite labs were installed at several area hospitals to perform spinal fluid testing.

The War Years and Blood Bank

The tremendous drain on manpower and resources resulting from World War II had a profound impact on SBMF. Shortly after his hiring in 1941, SBMF’s pathologist, Dr. Carl Culbertson, who would later succeed Dr. Giordano as director, took a leave of absence to join the Indiana University Medical Unit which was then dispatched overseas. One of the Laboratory’s medical technologists, Miss Bonita Carlson, resigned to take a post in Brazil to help develop rubber supplies and substitutes for the war effort. And the duties of staff pathologist, Dr. Joseph Haymond, required him to spend four days a week at Hurley Hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan, and only one day a week at SBMF.

Likewise, because of the scarcity of material resources during the war, all supplies and equipment were distributed on a priority basis. Desired materials had to be approved by a government agency, and then sent to the distributor.

Despite the challenges and setbacks the war presented, SBMF and the community at large rose to the occasion by setting up a civilian defense plasma bank. Local industry donated a blood bank centrifuge and freezer with a quick freeze compartment. The storage area of this deep freeze could accommodate up to 400 units of plasma at a temperature of -20°F. Hundreds of volunteers promptly came forward to donate blood. Bleeding and preparing the plasma were done in the evenings, and then stored for shipment to the armed forces. By 1946, the civil defense plasma bank was processing up to 500 units annually.

That same year, a natural progression occurred as the civil defense plasma bank evolved into a blood banking service. Then, in 1951, to better coordinate area blood needs, the Central Blood Bank was established as a separate entity under the auspices of the Junior League of South Bend.

By today’s standards, post-war blood needs were modest, but the establishment of the Central Blood Bank provided an invaluable breakthrough. Previously, blood was transfused directly from donor to patient. Now, blood could be donated, processed and stored for later transfusion. Furthermore, in an emergency, 15 to 20 donors could show up and have their blood drawn at the same time.

By 1966, the Central Blood Bank was collecting 6,000 units a year to meet the growing needs of the community. Three years later, in 1969, the Central Blood Bank merged with SBMF. Screening blood donors for hepatitis B virus (HBV) became federally mandated in 1972 and testing for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has occurred since the mid-1980s.

Today, the blood bank collects more than 20,000 units a year, at three donor collection centers housed in SBMF facilities. In addition to standard blood donations, SBMF can collect twice the amount of red cells (double red cells) or handle a platelet donation (platelet apheresis) for treating specific medical conditions.